.jpg) |

| Civil War Photographer, Matthew Brady's photo of Howell Cobb |

At the onset of the Civil War, the Federal government initially took a tough stance with the South. Lincoln and his administration wanted to avoid recognizing the Confederacy in any official capacity, including the formal transfer of military prisoners. The Lincoln administration softened their stance following the Battle of First Manassas or Bull Run, when the Confederate Army captured over 1,000 Union prisoners.

Fighting in Missouri during the months of October and November of 1861, had led to Union Major General John Frémont and Major General Sterling Price of the Missouri State Guard to approve their own exchange of prisoners, and agree to terms of the transfer of future captives. This displeased President Lincoln. For the most part, it was Lincoln's way or the highway. Lincoln relieved Frémont from his command on November 2, 1861 for authorizing his own prisoner exchange policy. Frémont's replacement, General David Hunter, refused to recognize Frémont's policy.

As the War continued, support for prisoner exchanges grew in the North. Petitions from Union prisoners captive in the South along with articles in northern newspapers put pressure on the Lincoln administration to seek a resolution with the South on the subject. On December 11, 1861, the United States Congress passed a joint resolution calling on President Lincoln to "inaugurate systematic measures for the exchange of prisoners in the present rebellion."

On February 23 and March 1 of 1862, two meetings were held between Union Major General John E. Wool and Confederate Brigadier General Howell Cobb to discuss the terms of a formal policy regarding the exchange of prisoners of war.

|

| Union Major General John Ellis Wool |

An arrangement between the United States and Great Britain during the War of 1812 provided a model for the negotiations. Several items discussed by Cobb and Wool were later adopted in the Dix-Hill Agreement, which was the formal agreement reached by both the Federal and Confederate Governments on the subject.

Differences between who's government would incur the cost of transportation hindered the negotiations. Another issue over how to handle a surplus of prisoners held by one side led to another problem the two men were unable to work out. General Cobb wouldn't agree to Wool's proposal of an even exchange of prisoners at the time of their meeting, while deferring the surplus issue to later negotiations.

Another meeting was held in June of 1862, this time between Confederate Brigadier General Howell Cobb and Union Colonel, Thomas Marshall Key, who was aide-de-camp to Union General-in-Chief, George B. McClellan.

|

| General George Brinton McClellan |

The meeting between Cobb and Key provides both historical and familial interest. First, as a lifelong Civil War buff, their meeting led to a doctrine that was accepted by both the Federal and Confederate governments regarding the important subject of prisoner exchange. Secondly because both these men are my distant cousins. There was no relation between the two men at the time of their meeting. A common relationship between the two wouldn't occur until the marriage of my 2nd Great Grandparents, William Allen Moss (Cobb side of the family) and Phebe Lucy Daniel (Key side of the family) in 1882.

Thomas Marshall Key was born in Mason County, Kentucky on August 8, 1819. He is my 2nd cousin 6x removed. By 1850, he had moved his family to Cincinnati, Hamilton County, Ohio where he served as a Democratic member of the Ohio Senate. The outbreak of the Civil War caused men from both sides to rally to their individual causes. Thomas Marshall Key accepted a commission as an Officer in the U.S. Volunteers Aide-de-Camp Infantry Regiment on June 20, 1861.

|

| Thomas Marshall Key's acception of promotion to Colonel |

|

| Thomas Marshall Key's acception of Aide-de-Camp position |

On August 19, 1861, Key was promoted to full Colonel and assigned to Union General-in-Chief, George B. McClellan's staff.

|

| President Lincoln, General McClellan and Colonel Thomas Marshall Key |

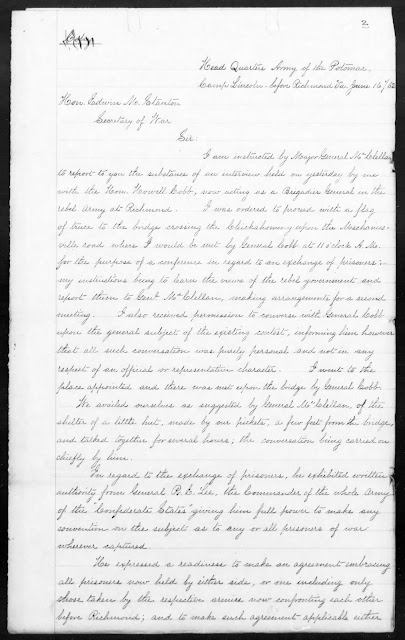

The meeting between Cobb and Key took place on June 15, 1862. During the meeting Cobb and Key again tried to reach an agreement regarding the exchange of prisoners. Colonel Key also discussed matters other than prisoner exchange, which pertained directly to the War. Key submitted a report to Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton summarizing his meeting with General Cobb. Colonel Key's letter to Secretary of War Stanton survived. Below are all seven pages of the letter followed by a transcription.

Head Quarters Army of the Potomac

Camp Lincoln before Richmond Va. June 16/62

Honorable Edwin M. Stanton

Secretary of War

Sir:

I am instructed by Major General McClellan to report to you the substance of an interview held on yesterday by me with the Hon. Howell Cobb, now acting as a Brigadier General in the Rebel Army at Richmond. I was ordered to proceed with a flag of truce to the bridge crossing the Chickahominy upon the Mechanicsville road where I would be met by General Cobb at 11 o' clock A.M. for the purpose of a conference in regard to an exchange of prisoners: my instructions being to learn the views of the rebel government and report them to Genl. McClellan, making arrangements for a second meeting. I also received permission to converse with General Cobb upon the general subject of the existing contest, informing him however that all such conversation was purely personal and not in any respect an official or representative character. I went to the place appointed and there was met upon the bridge by General Cobb.

We availed ourselves as suggested by General McClellan, of the shelter of a little hut, made by our pickets, a few feet from the bridge, and talked together for several hours, the conversation being carried on chiefly by him.

In regard to the exchange of prisoners, he exhibited written authority from General R. E. Lee, the Commander of the whole Army of the "Confederate States" giving him full power to make any conversation on the subject as to any or all prisoners of war, wherever captured.

He expressed a readiness to make an agreement embracing all prisoners now held by either side, or one including only those taken by the respective armies now confronting each other before Richmond; and to make such agreement applicable either to existing prisoners, or also those hereafter captured. He stated that he would sign any cartel which was based upon principles or entire equality and he proposed that exchanges should take place according to the date of capture; first-however exhausting the list of officers. The scale of equivalents to be any one which we might present and which would operate equally - for instance, the one exhibited to him by General Wood at a conference between them and which was taken from a cartel between the United States and Great Britain in 1812. The exchanged persons to be conveyed by the captors (at the captors expense) to some point of delivery convenient to the other party. The rule of exchange to operate uniformly without any right of reservation or exception in any particular case. He professed ignorance of any complaint against his Government in any matter of exchanging prisoners and pledged himself for the removal of any cause of complaint upon representation being made. He suggested propriety of releasing upon parole any surplus of prisoners remaining after the exchange had exhausted either party. I saw no evidence of any disposition to over reach me in this conference.

Our personal conversation began by my saying to him that - I was pleased to meet him upon a peaceful errand, and that nothing was so desired by me as that we might soon meet in permanent peace. He replied the permanent peace could at any time be established within half an hour. I told him that I would like to hear his views on that subject, and in return would give him mine. He at once expressed his desire for a general conversation. We both positively disclaimed any official or representative character and expressly promised that nothing said by either should be understood as any thing but the expression of individual sentiment; each being at liberty to repeat any portion of the conversation to his commanding General. He then began speaking and continued without interruption for more than half an hour. The drift of the discourse was, that the invasion of the seceding States with it's consequent slaughter and waste had created in the Southern mind such feelings of animosity and spirit of resistance that the war could only end in separation or extermination, that a treaty of peace could at once be agreed upon, but that re-union could be effected only by subjugation and permanent military occupation. I told him briefly in reply that his statement surprised and grieved me. That it must be well known to the people of the South the the whole purpose of the Government was to support the Constitution, and to enforce alike upon all in every State, the laws of the United States; that I had hope and supposed that the Confederate leaders at least had been impressed by a sense of hopelessness of the struggle; that the unequal character of the contest, our greater numbers, wealth, credit and resources of all kinds - the unanimity of the free States and determination evinced by their entire population - the established loyalty of Maryland, Western Virginia, Kentucky and Missouri - the Union sentiment manifested in Tennessee, and known to exist in greater or less degree throughout the South - the hopelessness of foreign intervention - the complete establishment of Sea and River blockades - the loss of position after position in the interior - and the certainty of our irresistible advance, had satisfied them that the continued resistance must be unavailing. To this he said he would reply "serration"; and he did so at great length; not controverting very much my statement of their condition, but denying that there was Union sentiment left in the planting region, especially in South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, or Louisiana (outside of the foreign element in New Orleans) or that it existed to any considerable extent in Eastern Va, North Carolina or even Tennessee; he said that food and arms made sufficient material for war - that the slaves had never so tractable as now - that slave labor was directed almost exclusively to the production of food, especially in Districts remote from military operations - and that every State had its manufacturers of arms and powder. He claimed that the military strength of the Confederate States was yet unbroken - that our Army before Richmond was not strong enough to force an entrance into it - that he was opposed to defending the town, but that his superiors had determined to do so, and we could only take it when they saw fit to abandon it. He asserted that if we took Richmond and every other important point in the "Confederate States" we would have gained nothing - that it would require years to suppress organized resistance and that at last we would be compelled to hold the country by military occupation, and that every military position would be surrounded by a hostile population.

I told him in reply that such a state of things as he had last described, would involve the part of the United States measures of military necessity and security not now contemplated - that the Army of the Potomac was so composed and in such condition that on the day when it moved upon Richmond, it would enter it even if opposed by the entire forces of the Confederate States - and that it was impossible for the seceding States to organize an Army any where which the United States could not break to pieces in a single engagement - that on the question of Union, the whole people of the North moved in solids - and that I could not sufficiently express their determination to enforce throughout the whole country the equal operation of the Federal laws - that I did not believe the people of the South, meaning free white citizens, were opposed to the United States Government - that I believed the secession movement proceeded from a class of men who had arrogated to themselves superior social positions and who intended to frame a Government in which they could grasp and hold political power - and that in my opinion of his views as to the future should prove correct, it might become necessary to disorganize that condition of society which gave rise to that class of power, and to raise up orders of laboring and middle class white men who would be loyal to the Union. He said with much excitement, that no men could be found in the original seceding States who could be made into a loyal class. I replied that we could find material enough in those States and that any amount of it would go there on our invitation.

Here we ceased conversation on general matters and returned to the particular subject of our meeting - the result of which I have already given. I subsequently said to him; every day's experience must show to your intelligent men that they your people are fighting their friends - that neither the President, the Army, or the people of the loyal States have any wish to subjugate the Southern States or to diminish their constitutional rights - our soldiers exhibit but little animosity against yours - the prevailing sentiment among them is a conviction of duty - I cannot understand the grounds upon which you leaders continue this conflict. He said - the election of a sectional President whos views on slavery were known to be objectionable to the whole South, evinced a purpose on the part of the Northern people to deprive the people of the South of an equal enjoyment of political rights - we cannot now return without degradation or with security - the blood which has been shed has washed out all feelings of brotherhood. We must become independent or conquered. I replied mutual bravery shown in battle never yet of itself permanently alienated the combatants; it produces mutual respect - a return to the Union, even upon the grounds of unequal forces would not involve degradation. The security of the South would be greater than before. The slavery question has been settled. it is abolished in the District - and excluded from the Territories - as an element of dissension slavery can not again enter into our national politics. The President has never gone beyond this in any expression of his views - he has always recognized the obligation of the Constitutional provisions as to fugitive slaves and that slavery within and between the slave States is beyond Congressional intervention - such is the political creed of the great body of the Republican party - no political organization at the North would be respectable in numbers which purposed Federal legislation or action in violation of the Constitution or in excess of it's powers. I told him that speaking for myself alone, I would express the opinion that this wretched strife should be at once ended by submission on the one side and amnesty on the other; and that Proclamations to that effect by Mr. Davis and Mr. Lincoln would be sustained by the great mass of the whole nation.

He replied, that no Confederate leader could openly advocate such a proposition and continue to live - that uttered among soldiers or citizens he would at once be slain. He said that the South might suffer much but it would ultimately succeed - that the struggle had but begun. This closed our conversation except that he expressed his readiness for another conference whenever Genl. McClellan or the Government should authorize the making of a cartel.

His manner was very courteous and he conversed free and earnestly and with apparent frankness. He mentioned the order of General Butler, relative to females in New Orleans and in doing so evinced much feeling - he said that all Southern men regarded it as they would a direct insult offered to their mothers, sisters and wives.

Gen. Cobb's brigade is in the front where the skirmishing is constant. He was well dressed and bore no appearance of frustration or discouragement. I will venture to state the impressions made upon my mind by the interview - they are these; That the rebels are in great force at Richmond and mean to fight a general battle in defense of it- that the Confederate leaders have no the power to control the movement which they have inaugurated - that there is little hope of reconstruction so long as the rebels have a large army in the field anywhere - that it may be found necessary in particular States, if not all, to destroy the class which has created the rebellion, by destroying the institution which has created them.

Trusting that I may not be considered as having committed any impropriety in the interview or in the communication, I am

Very respectfully

Your obdt servant

Thomas M. Key

Colonel and Aide-de-Camp

|

| Secretary of War Edwin McMasters Stanton |

Secretary of War Stanton was vehemently upset that Key discussed other items with Cobb. In a letter to General McClellan, Stanton commented that "it is not deemed proper for officers bearing flags of truce in respect to the exchange of prisoners to hold any conference with the rebel officers upon the general subject of the existing contest or upon any other subject than what relates to the exchange of prisoners."

Presumably due to Key's discussion of topics other than prisoner exchange, Stanton appointed Union Major General John A. Dix to conduct the next round of cartel negotiations. The meeting was to take place on July 8, 1862. By this time, Confederate General Howell Cobb was too ill to attend. Robert E. Lee named General Daniel Harvey Hill to take his place. Their meeting would lead to the Dix-Hill Cartel, which served as the foundation of principles used to facilitate prisoner exchange for the remainder of the War. Several of my relatives on would later reap the benefits of the Dix-Hill Cartel.

|

| Burial Record for Thomas Marshall Key |

Here's my relation to Thomas:

Thomas Marshall Key (1819 - 1869)

is your 2nd cousin 6x removed

Marshall Key (1783 - 1860)

Father of Thomas Marshall

James Key (1740 - 1817)

Father of Marshall

Martin Key (1715 - 1791)

Father of James

Elizabeth Key (1746 - 1821)

Daughter of Martin

William Ford Daniel (1774 - 1848)

Son of Elizabeth

L. Chesley Daniel (1806 - 1882)

Son of William Ford

William Henry "Buck" Daniel (1827 - 1896)

Son of L. Chesley

Phebe Lucy Daniel (1862 - 1946)

Daughter of William Henry "Buck"

Valeria Lee Moss (1890 - 1968)

Daughter of Phebe Lucy

Phebe Teresa Wheeler Lewis (1918 - 1977)

Daughter of Valeria Lee

Joyce Elaine Lewis (1948 - )

Daughter of Phebe Teresa

Chip Stokes

You are the son of Joyce

No comments:

Post a Comment