|

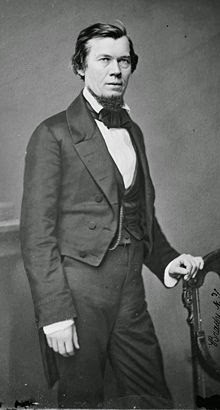

| Colonel Robert Granderson Cole |

The Cole brothers were born in Manchester, Chesterfield, Virginia. Their sister, Sarah A. Cole is my 3rd great grandmother. Their father, George W. Cole was a veteran of the War of 1812. Their grandfather, Hamblin Cole was a patriot in the American Revolution. Their mother, Caroline Wooldridge's family owned and operated the Midlothian Coalmines in Virginia from as early on as 1730. Coming from good stock, the Cole brothers were destined for success.

Archibald "Archie" Hamblin Cole was born in Manchester, Chesterfield, Virginia on January 30, 1812. Not much is know about his early years. By 1830, he had relocated to Anderson, South Carolina where is is listed in the 1830 and 1840 Federal Census. Sometime after 1840, he made his way to the Florida territory. In the early 1840's, Archie lived in Duval, Florida with a prominent mixed race woman named Susan Clarke. Archie and Susan had two children together, Mary Laura Cole born in 1842 and John Henry Cole born in 1846. Archie and Susan separated sometime after the birth of John Henry. By 1848, he had acquired property in Putnam County, Florida. On May 15, 1848, Archibald married Annie Lamar Mays. Archie and Annie also had two children together, Sarah Cole born in 1854 and Archibald Wooldridge Cole, who was born in 1859 and sadly died in 1861. Archie was a founding member of the original Florida Historical Society, started by Benjamin A. Putnam in 1856.

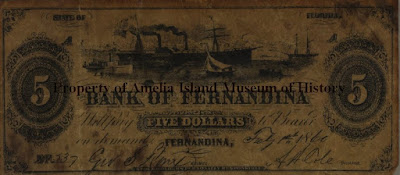

Prior to the Civil War, he owned and operated a large citrus plantation in Orange Mills. In 1850, he had as many as 50 enslaved workers on his plantation. He and a man named John Reardon had also opened a general store in Fort King, Florida and made it into a post office. Archie was also an investor in the Florida Railroad Company. In 1859, Archie helped establish the Bank of Commerce at Fernandina. He is listed as on of the three original commissioners of the bank. He was also the bank's first president.

|

| 1860 $5 Bank Note Signed By President A.H. Cole |

On January 10, 1861, The State of Florida officially seceded from the United States. They were officially admitted to the Confederate States of America on April 22, 1861. Archibald's ties to Florida and Virginia caused him to cast his lot in with the Confederates. He made his way to Virginia where he placed his services in the hands of General Joseph. E. Johnston. His first duties were acting as a Volunteer Aide-de-Camp where he acted as Quartermaster during the Battle of First Manassas. He entered the Confederate Army with the rank of Major. Shortly after this, he was promoted to Inspector of Transportation of the Army of Northern Virginia. When Johnston took a bullet to the shoulder and a shell fragment to the chest at The Battle of Seven Pines on June 1, 1862, command of the Army of Northern Virginia was passed to Robert. E. Lee.

On May 4, 1862, Major Archibald H. Cole wrote an order to Captain W. S. Wood requesting eight artillery horses for the Stuart Horse Artillery.

|

| Letter from Major Cole to Captain Wood |

|

| General Orders No. 76 showing Archie's promotion |

Archie continued to perform Inspector of Transportation duties for Lee until October 17, 1862 when he was promoted to Chief Inspector General of Field Transportation for all of the Confederate Armies. In this role he would be responsible for recruiting, buying, and recuperating horses. Archie was based out of the Confederate capitol of Richmond. Archie immediately tried to purchase 1,000 horses from Texas. By March of 1863 only about 700 had been obtained and they were still located in Louisiana. Horses were in short supply. In December of 1862, Lee wrote Confederate Secretary of War James A. Seddon to request permission to transfer horseless cavalrymen to infantry units. Lee was not a fan of the practice of cavalry soldiers returning home on furlough to obtain new horses. He believed he should have every man in the field possible and that it would make the men in the cavalry be more careful with their mounts. Lee's army spent the winter of 1862-1863 near Fredericksburg, where lack of forage caused Lee to disburse parts of his army to the Shenandoah and parts of North Carolina to look for supplies.

Horses were in short supply and many horses continued to disappear in the south due to confiscation by the Federal and Confederate armies. On May 13, 1862, The Richmond Enquirer estimated that farmers had lost a third of their horses and mules, "thus leaving them without sufficient force to cultivate even ordinary crops." To combat the confiscations, Lee added impressments to the list of Major Cole's responsibilities. All field officers except for those of army commanders were forbidden to confiscate horses. Impressments were not popular with the locals due to the government only paying half price for the animals. The Confederate government tried to address this issue by increasing the prices offered for horses, however inflation ran higher than the increases. Between December of 1862 and February of 1864, Archie was only able to collect 4,929 horses and mules from the State of Virginia. Prior to the war, Virginia boasted that she had more than 250,000 horses and mules. This was no where near Lee's request for 7,000 horses and 14,000 mules needed for the artillery and cavalry for the Army of Northern Virginia.

In April of 1863, the war came to his property at Orange Mills. The Official Records of the Civil War included a letter dated April 2, 1863 from Palatka citizen Thomas T. Russell to Confederate Brigadier General Joseph Finegan who was in command of Middle and East Florida. I've included the letter in its entirety below:

THOS. T. RUSSELL. To Brigadier General JOSEPH FINEGAN;

RESIDENCE, EAST BANK SAINT JOHN'S [RIVER],

Near Palatka, Fla., April 2, 1863.

Brigadier General JOSEPH FINEGAN:

SIR: On Monday, the 23 ultimo, a large side-wheel steamer came up the river as far as Palatka and fired four shells over the town. She then returned to Orange Mill, and lay off that place until 2 o'clock Tuesday evening, and went down the river. While at the mill the Yankees butchered a beef, killed several sheep, and took on board a Negro man named John, belonging to Mr. Frank Hernandez.

On Thursday morning a large propeller came up the river and lay off the mill until evening, when she came up opposite Palatka, abreast of the residence of Mr. Antonio Baza. A large force of Negroes was landed from the propeller at the residence of Mr. C. Dupont, and also at Orange Mill, which said force marched by land to Mr. Baza's and Mr. Sanchez's place, opposite Palatka, where they joined the force on board the propeller. This force by land visited the plantation of Colonel Dancy and caught two of his Negroes, one of which afterward escaped. They cooked and ate at this place and carried off all the

poultry. The colonel's place on the river was also ransacked by the Negroes. They also visited the plantation of Major Balling, destroying all they could, but did not succeed in getting any Negroes, as, fortunately, they had been removed a few days previous. This land force, on arriving at the residences of Messrs. Sanchez and Baza, surrounded the places, and took 3 Negroes from Mr. Morris Sanchez and other things of value from the yard. They did not succeed in catching Mr. Baza's Negroes, but took from him three horses and one cart, all of his poultry, hogs, pots, salt, and everything else they could lay their

hands upon. They also butchered two beeves in the yard. The Negroes kept the houses surrounded, and abused and insulted the women just as they pleased. They encamped that night on the banks of the river in Mr. Baza's field. On Friday morning the propeller started and proceeded slowly over to Palatka

and went up to the wharf, landed a number of men on the wharf, and was in the act of landing some artillery, when Captain J. J. Dickison and his company, who had been patiently waiting, fired into them. The propeller then, as fast as steam could carry her, backed out from the wharf, firing shell, grape, canister, and small-arms. After they fired for a while she proceeded over the river to Mr. Baza's point, and communicated with a company of Negroes that had been left over there. The company of Negroes then proceeded back by land to Orange Mill, and the propeller went back down the river and took them on board. Every vestige of furniture was taken by the Negroes from the residences of Dr.

R. G. Mays, Major E. C. Simkins [quartermaster], and Major A. H. Cole [quartermaster]. Mr. Antonio Baza was taken prisoner by the Negroes, but succeeded in making his escape. The Yankees on the way down the river again stopped at the residence of Mr. C. Dupont and demanded the Negroes who were

hid, stating if the Negroes were not immediately delivered they would burn the houses. Mrs. Dupont, who was much alarmed, accordingly delivered up the negroes, against the wishes and urgent appeals.

In a conversation with Colonel Montgomery, of the Negro regiment (I having been surrounded and taken prisoner, but afterward released), he informed me that he had come up for the purpose of permanently occupying Palatka, and that they intended restoring Florida to the Union at all hazards; that he would have a force of some 5,000 men at Palatka in a few days; that they had been acting in

a mild way all along, but that they intended now to let us feel what war actually was; that the United States marshal for Florida was along and pointed him out to me; that all the Negroes were declared free and he intended to take all he could find.

Thus you will perceive, general, what we are to expect, and had it not been for the brave and gallant conduct of Captain Dickison, his officers and men, Palatka would this day have been in possession of the Negro enemy. Captain Diskison has been one of the most untiring and energetic officers I have ever

met with. He is always on the alert, and had he sufficient force would never let the enemy land on either side of the river up here. I visited Palatka since the propeller left, and from the great quantity of blood about on the wharf and pieces of bones picked up many of the enemy evidently were killed. Every bullet fired by Captain Dickinson's men must have took effect. This company deserves the thanks of the people of Florida and the Government, for I think they have well merited the same.

Allow me, general, to suggest to you the propriety of taking some action in regard to the vast quantity of cattle on the east side of the Saint John's, as the enemy are continually butchering for the use of their troops, and as the citizens are entirely helpless to defend themselves.

All of which is respectfully submitted by your obedient servant,

THOS. T. RUSSELL

Unfortunately for the Confederates, the war contained multiple fronts where horses and mules were needed. When Braxton Bragg was defeated at the Battle of Chattanooga, Joseph E. Johnston assumed command of the Army of Tennessee. Johnston was able to address the artillery's horse shortage of 600 horses by reducing the number of horses hauling each gun to four from six. This reduced their speed and expedited their exhaustion.

Archibald Cole was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel on February 2, 1864. In April of 1864, Archie proposed "to cover all the ground in Alabama and Georgia and get everything needed for the plow." Archie believed that the only way to supply Lee and Johnston's armies with fresh mounts for the spring was to reduce the transportation allowance and transfer the current stock of animals from secondary armies to the main armies in Georgia and Virginia. Unfortunately for the Confederates, this didn't happen. Johnston's lack of horses tied him to the railroad which allowed Federal Major General William Tecumsah Sherman to continually harass his flank.

By February of 1865, Archie estimated the remaining armies of the Confederacy needed 6,000 horses and 4,500 mules: "The number to be procured in the Confederate States east of the Mississippi by impressment depends on the decision which may be made as to the quantity of animals the farmers will be allowed to keep as essential to their operations. I estimate the supply to be obtained from all sources (provided I am furnished means) not to exceed 5,000 animals on this side of the Mississippi. This leaves a deficit of 5,000 to fill my estimate. If the horses are not supplied the military operations are checked and may be frustrated. If the farmers are stripped of a portion of the animals essential to the conduct of their agricultural operations there must be a corresponding reduction of supplies of food for man and horse." Archie also continued to suggest that animals might be procured from Mexico or behind Union lines. On March 31, 1865, Archie was re-assigned to the Department of Florida where he would remain until the end of the war.

|

| Confederate Officer's Index Card for A.H. Cole |

Archibald Cole returned home to Orange Mills, Putnam County, Florida . He made his oath of allegiance to the United States on May 29, 1865 and was pardoned by President Andrew Johnson on March 29, 1866.

|

| Archibald Hamblin Cole's Presidential Pardon |

Archibald Hamblin Cole lived an additional 14 years after the Civil War. At the time of his death, he was 66 years old. He died on February 3, 1879 and is buried in his second wife's family cemetery in Orange Mills, Putnam County, Florida. From the little information I have found, it appears as though this cemetery may have fallen victim to development. I found an article on putnam-fl-cemeteries.org that stated the headstones had been removed and possibly bulldozed into the river. This was according to a survey that was done in 1999. The last time the headstones were seen at their original location was sometime in the early to mid 1990's. The bodies were not removed and remain buried there. I was able to locate an old picture of Archie's headstone. Apparently the headstones were removed in the 1970's and relocated to a nearby cemetery belonging to the Braddock family. The headstones were then relocated to St. John the Evangelist Cemetery that was established in East Palatka in 1881, where they are currently located. A descendant the Mays family, Mary Murphy-Hoffmann owns the St. John the Evangelist Cemetery. She has hopes of relocating the grave markers back to the Mays-Simpkins-Cole cemetery, which is only a few miles away.

|

| Archie Cole's Obituary |

|

| Mays-Simpkins-Cole Cemetery |

|

| Archibald Hamblin Cole's Gravestone |

Here's my relationship to Archie:

3rd great-granduncle

Father of Archibald Hamblin Cole

Daughter of George W. Cole

Son of Sarah A. Cole

Son of George Patterson Vaden

Son of William Austin Vaden

Daughter of Robert William Vaden (Lewis)

You are the son of Joyce Elaine Lewis

Robert Granderson Cole was born in Manchester, Chesterfield, Virginia on September 25, 1830. Robert grew up on his familial lands in Virginia. He enrolled in the United States Military Academy at West Point on July 1, 1846. Robert graduated 37th out of 44 cadets in the Class of 1850. Following his graduation he entered the United States Army on July 1, 1850 with the rank of Brevet Second Lieutenant of Infantry. He would head to the west to begin his service. Robert's first assignment was Fort Washita in Oklahoma Territory. Here he would perform frontier duty from 1850-1851.

|

| Fort Washita Blockhouse |

Robert was next assigned to Fort Gates in Coryell County, Texas. Fort Gates has been established in 1849 on the Military Post Road between Austin and Fort Graham as a protection of the frontier against hostile Indians. Robert performed scouting duty here from 1851-1852. Fort Gates was abandoned in March of 1852 as the frontier line had advanced further west.

|

| Marker at the Site of Fort Gates |

In 1852 after the abandonment of Fort Gates, Robert was reassigned to Camp Johnston further west on the frontier. Camp Johnston was a temporary U.S. Army Camp that had been established in March of 1852 in Tom Green County, Texas. The camp was named after Captain Joseph E. Johnston, who was Chief Topographical Engineer of the Department of Texas from 1848-1853. This was a temporary camp that was established for five companies of the 8th U.S. Infantry. The camp was located on the south bank of the North Concho River near the present day town of Later Valley. It was home to some 284 troops and their families until it was abandoned on November 18, 1852.

|

| Officer's Barracks, Fort Chadbourn |

Robert was promoted to Second Lieutenant 8th U.S. Infantry on May 25, 1862. He remained at Fort Chadbourn until 1853 when he was transferred to Fort McKavett in Menard County, Texas. Fort McKavett had been established in March of 1852 to protect frontier settlers and travelers on the Upper El Paso Road. It was first known as Camp San Saba, but was renamed for Captain Henry McKavett, who was killed at the Battle of Monterey on September 21, 1846.

|

| Remains of a Barrack at Fort McKavett |

In 1853, Robert was transferred to the Ringgold Barracks near present dat Rio Grande City, Texas. The Ringgold Barracks, later known as Fort Ringgold, was the southernmost installation of the western tier of forts that were constructed at the end of the Mexican War. The fort had been established on October 26, 1852 by two companies of the 8th U.S. Infantry. It was named after Brevet Major Samuel Ringgold who was the first U.S. Army Officer to die from wounds received in the Battle of Palo Alto on May 8, 1846. Robert was based out of the Ringgold Barracks from 1853-1854. In 1856, Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee visited Ringgold Barracks for court-martial duty. The house Lee stayed in has been preserved.

|

| "Robert E. Lee House" at Ringgold Barracks |

In 1854, Second Lieutenant Cole moved to Fort Davis, located in present day Jeff Davis County, Texas. Fort Davis had been established on the order of General Persifor F. Smith on October 23, 1854. It was named after then Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis. The fort was strategically located to protect emigrants, mail coaches and freight wagons on the Trans-Pecos portion of the San Antonio-El Paso Road. The fort was originally garrisoned by Lieutenant Colonel Washington Seawell and six companies of the 8th U.S. Infantry. The fort was home to over 400 officers and enlisted men. Cole performed scouting duty out of Fort Davis from 1854-1855.

|

| Map of Fort Davis, 1856 |

Robert was promoted to First Lieutenant, 8th U.S. Infantry on September 4, 1855. He was transferred to Fort Bliss, which was located on the absolute western part of Texas. Fort Bliss had been established on November 7, 1846 by General Orders #58 as Post at El Paso in present day El Paso, Texas. The fort was first garrisoned by Brevet Major Jefferson Van Horn and was home to six companies of the 3rd U.S. Infantry. The fort was renamed for Brevet Lieutenant Colonel William Wallace Smith Bliss in 1854. Robert performed scouting duty out of Fort Bliss from 1856-1857 and Fort Davis in 1857.

|

| Recreation of Old Fort Bliss |

Robert performed recruiting services in 1858-1859. He was assigned to duty performing a Coast Survey from May 19, 1859 through January of 1861. On January 28, 1861, First Lieutenant Robert Granderson Cole tendered his resignation to the United States Army.

On February 23, 1861, First Lieutenant Robert Granderson Cole wrote the following letter to Jefferson Davis:

Montgomery, Ala

Feb 23 1861

His Excellency

The President of The Confederate States of America

Sir,

I have the honor respectfully to apply for an appointment in the Army of the Confederate States of America. I graduated at West Point in 1850. Have been a First Lieutenant since 1855. Nearly the whole of my eleven year service has been with my Company on the frontier of Texas.

I have the honor to be with great respect

Your obedient servant,

Robert G. Cole

First Lieutenant, 8th US Infantry

|

| Letter from Robert G. Cole to Jefferson Davis |

In March 16, 1861, he was commissioned as a Captain of Infantry on the staff of Brigadier General Robert Seldon Garnett. Garnet had served the U.S. army in the Mexican War and the Seminole Wars in Florida. In 1849, while stationed at the Presidio of Monterey, he designed the Great Seal of California. He resigned his commission in April of 1861 and became Adjutant General of the Virginia troops, under Robert E. Lee.

|

| Robert Selden Garnett |

In June of 1861, Garnett was promoted to Brigadier General. Garnett's promotion was also good for Cole. On June 18, 1861 Robert Granderson Cole was promoted to Major. At the beginning of the Civil War, Federal forces crossed the Ohio River and seized a portion of northwestern Virginia (now West Virginia). On June 15, Robert E. Lee assigned Garnett to reorganize the Confederate forces in the area. He deployed his forces at strategic points along the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike in hopes to defend the vital supply line. A series of small skirmishes occurred and forced the Confederates to withdraw under pressure from George B. McClellan's Federals.

Garnett's forces were defeated at the Battle of Rich Mountain on July 11, 1861. Following the loss, Garnett withdrew from his Laurel Hill trenches under cover of darkness, in hopes to escape to northern Virginia with his 4,500 men. He redirected his withdrawal after receiving false reports that his escape route to Beverly was blocked by Federal troops. He instead marched northeast and was pursued by as many as 20,000 Union troops. While direction his rear guard in a delaying action at Corrick's Fordm Garnett was shot and killed by a Union volley.

Garnett's death resulted in Cole being transferred to the staff of Brigadier General William Wing Loring on August 6, 1861. Cole remained in this position until December 24, 1862 when he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and placed in charge of the Subsistence Department on the staff of General Joseph E. Johnston. On July 5, 1862, Robert was promoted Chief Commissary Officer for the Army of Northern Virginia. He would remain on Robert. E. Lee's staff through the surrender at Appomattox.

|

| Robert E. Lee and His Staff, Lt. Col. R.G. Cole is No. 2 |

The position of Chief Commissary Officer was not a glamourous one. He would never gain glory on the field of battle. Instead he would labor continuously to keep 65,000 men and horses fed. Lieutenant Colonel Cole pressed on despite the shaky infrastructure of the new Confederate States of America. A Federal Naval blockade and multiple Union armies squeezing in on all sides only further complicated his job. Persistent shortages in food, clothing and horses plagued Lee's army.

On May 29, 1863, in accordance with an Act of Confederate Congress, General Orders No. 70 officially abolished the office of Regimental Commissary. Duties of the Regimental Commissary officer now fell to the Regiment's Quartermaster. Thankfully a Commissary Sergeant could be retained to assist the already busy Quartermaster. The "best qualified Regimental Commissary" of the brigade was also allowed to become an assistant to the Brigade Commissary Officer. Roughly a forth of the Regimental Commissary Officers were guaranteed a new assignment within their department. The rest of the men would either be reassigned or dropped from the rolls at the earliest date possible. The deadline for reassignment was July 31, 1863.

Lieutenant Colonel Cole immediately pushed back. On June 1, he fired off a letter to the Adjutant Inspector General Lieutenant Colonel S. Cooper, requesting the order to be modified to allow cavalry Regiments to retain their Assistant Commissary Officer since they frequently conducted independent operations. Cole saw no issue with an additional assistant for the Brigade's Commissary Officer, however he requested each Corps and Division Commissary to be allowed to have two such assistants. He painstakingly identified a list of fifty two Regimental Assistant Commissary Officers who should be retained and reassigned to later positions. Cole's proposal would create several additional positions for former Regimental Commissary Officers. Robert E. Lee congratulated Cole after the Gettysburg campaign for this ability to provide the army with flour during the incursion into the north..

Another problem Cole faced was politics. The Confederacy's Commissary General and long time friend of Jefferson Davis, Colonel Lucius B. Northrop was stingy and at times uncooperative at best. A letter from Cole to Northrop date November 30, 1864 states:

Colonel,

I find that much complaint is arising upon the subject of the bread ration. It is generally thought to be too small & now especially as the season for vegetables is over. Is is alleged also that much dissatisfaction leading to desertion among the men is increasing. I had a conversation with General Lee upon the subject today and he is very desirous that the ration of Meal, especially, be increased. From what I can learn myself I think this is advisable if within the limits of our ability to keep up the supply. General Lee requested me to write to you upon this subject and I take the liberty to urge some increase if practicable.

I am Col. very respectfully your obedient servant,

R. G. Cole

Lt. Col.

Northrop provided no help. He congratulated himself for having lowered the bred ration a few months prior. Had he not done so, he asserted, Lee's army would have been starving. The Army of Northern Virginia continued to face supply problems. By February of 1865, Lieutenant Colonel Cole observed "there was no meat to be had for the men still under siege at Petersburg." In just a few short months, the war would be over. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Granderson Cole surrendered with Robert E. Lee at Appomattox on April 9, 1865. His parole read as follows:

We, the undersigned Prisoners of War, belonging to the Army of Northern Virginia, having been this day surrendered by General Robert E. Lee, C. S. A., Commanding said Army, to Lieutenant General U.S. Grant, Commanding Armies of the United States, do hereby give our solemn parole of honor that we will not hereafter serve in the armies of the Confederate States, or in any military capacity whatever, against the United States of America, or render aid to the enemies of the latter, until properly exchanged, in such manner as shall be mutually approved by the respective authorities.

|

| Confederate Officer's Index Card for R.G. Cole |

Following the Civil War, Robert moved to Palatka, Florida where he helped run the citrus plantation with his brother Archie. He also maintained a business in Savannah, Georgia. He also continued his friendship with Robert E. Lee. As Lee's health began to fail in the winter and spring of 1870, he was persuaded to take a trip to the deep South. Lee made the trip with his daughter, Agnes. He wrote a letter to his wife on April 18, 1870 stating:

I returned from Florida Sunday, April 16th, having had a very pleasant trip as far as Palatka on the St. Johns. We visited Cumberland Island, and Agnes decorated my father's grave with beautiful fresh flowers. I presume it is the last time that I shall be able to pay to it my tribute of respect. The cemetery is unharmed and the grave is in good order, although the house at Dungeness has been burned and the island devastated. Mr. Nightengale, the present proprietor, accompanied me from Brunswick. We spent a night at Col. Cole's, a beautiful place near Palatka and ate oranges from the trees. We passed some other beautiful places on the river but could not stop at any place but Jacksonville, where we remained from 4 P.M. to 3 A.M. next morning, rode over the town and were hospitably entertained by Col. Sanderson. The climate was delightful. the fish inviting and abundant.

The Cole home that Lee visited in 1870, was one the east bank of the St. John's several miles south of Federal Point, at Orange Mills. It was the pre-Civil War home of Col. Cole's brother, Archibald H. Cole.

The Palatka Herald of April 20, 1870 wrote:

General Lee paid our county a visit on the last trip of the Nick King. He spent the night with Colonel Cole at Orange Mills. Our citizens would have been glad to have had the honor of his presence, but in this they were disappointed. Whether here, or in Virginia, General Lee will live in the hearts of his countrymen.

Robert E. Lee died in Lexington, Virginia on October 12, 1870. He was mourned by all of his countrymen. Robert Granderson Cole was among the many who donated to have the Recumbent Statue of General Robert E. Lee placed at Lee Chapel in Lexington. Cole's donation of $100 in 1879 was a considerable amount of money at the time.

|

| Recumbent Statue of Robert E. Lee, Lee Chapel, Lexington |

Robert Granderson Cole lived an additional 22 years following the end of the Civil War. He never married. He was 57 years old when he died. Cole died in Savannah, Georgia on November 7, 1887. He is buried in Bonaventure Cemetery.

|

| Robert Granderson Cole's Obituary |

|

| Robert Granderson Cole's Tombstone |

Here's my relationship to Robert:

3rd great-granduncle

Father of Robert Granderson Cole

Daughter of George W. Cole

Son of Sarah A. Cole

Son of George Patterson Vaden

Son of William Austin Vaden

Daughter of Robert William Vaden (Lewis)

You are the son of Joyce Elaine Lewis

|

| Chandler Cox Yonge |

Archie and Robert's sister, Julia A. Cole was married to Major Chandler Cox "C.C." Yonge who also served as a Quartermaster during the Civil War. Chandler Cox Yonge was born on October 3, 1818 in Fernandina, Florida when it was still a Spanish possession. He attended the University of Georgia and graduated in the class of 1833. Following his graduation, he practiced law in Pensacola, Florida. In 1838, C. C. served as an assistant secretary for the first Florida Constitutional Convention. He served on the first Florida Senate and helped write early Florida law. In 1845, President James K. Polk appointed C.C. to the office of District Attorney for Florida. Yonge held this position under Presidents Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan. He married Julia A. Cole on May 18, 1848 in Madison, Florida. When Florida seceded from the Union in January of 1861, C.C. initially served as District Attorney for the Confederacy. He served in this capacity through August of 1863. In August of 1863, Yonge attained the rank of Major and served the Confederacy as a Quartermaster through the end of the war. His headquarters were in Tallahassee.

Chandler Cox "C.C." Yonge lived an additional 24 years following the end of the Civil War. He was 70 years old at the time of his death. He died in Pensacola, Florida on February 17, 1889. He and his wife, Julia are buried in the Saint Michael's Cemetery in Pensacola, Florida.

|

| Julia Cole Yonge and C.C. Yonge With Their Family |

Julia A. Cole was born in Manchester, Chesterfield, Virginia on June 30 1832. She met her future husband in Orange Mills, Florida at the home of her brother, Archibald Hamblin Cole. Julia and C.C. had six children. They were the parents of Philip Keyes Yonge, who was a successful career in the lumber industry in Florida. Julia was 78 years old at the time of her death. She died in Pensacola, Florida on September 17, 1910

|

| Graves of C.C. Yonge and Julia Cole Yonge |