|

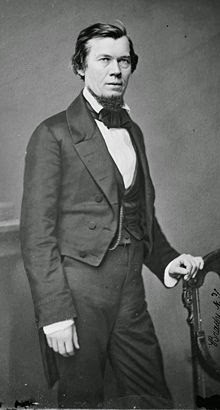

| Captain Robert Cobb Kennedy |

By the summer of 1864, there were factions in both the North and South who had grown weary of the war and were eager for peace. The re-election of Abraham Lincoln was in doubt. Forces in the Confederate Government hoped to seize an opportunity in the North to create widespread panic on the scale of the New York City Draft Riots of the previous year. Jefferson Davis now aimed to create a second war front behind Northern lines. A vocal group of anti-Lincoln Democrats in the North, known as Copperheads, opposed the Civil War and wanted to make a peace settlement with the South. Jefferson Davis had received word through secret coded letters that nearly as many as 500,000 Copperheads were waiting in Northern states for someone to help form them into an army. Davis hoped to plant enough seeds amongst the Copperheads to inflict serious damage to the North from the inside.

|

| Jacob Thompson |

Davis ordered Jacob Thompson to lead a delegation of Confederate operatives to Canada where they would organize anti-Union plots. Thompson had resigned as the United States Secretary of the Interior at the outbreak of the Civil War and had previously served as Inspector General of the Confederate States Army. In Canada, he would assume the leadership of the Confederate Secret Service operations in the area. The Canadian government didn't care what the Confederates did in Canada as long as no Canadian laws were violated.

In May of 1864, Thompson arrived in Montreal, Canada and began to hatch several plots against the United States. On June 13, 1864, he met with former New York Governor, Washington Hunt, at Niagara Falls and discussed forming a Northwestern Confederacy in Indiana, Illinois and Ohio (apparently those three states were said to have the largest Copperhead contingency). Thompson also received money to buy arms, which he gave to Benjamin Woods, owner of the New York Times. He also arranged the purchase of a steam ship, which he intended to arm with the purpose of harassing shipping efforts in the Great Lakes region.

In September, Thompson directed a failed plot to free Confederate prisoners of war that were being held at Johnson's Island near Sandusky, Ohio and Camp Douglas, near Chicago, Illinois. Thompson had hoped that the "Copperhead Army" would materialize and aid in this plan, but that proved to be wishful thinking. The "Copperhead Army" would in fact, never materialize. Numerically the "Copperhead Army" would have been about 5 times the size of the Union Army of the Potomac and about 8 times the size of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia.

Frustration began to set in for Thompson. Unable to achieve the creation of a Northwestern Confederacy and unable to raise an army of Copperheads, Thompson turned his sights on trying to disrupt the Presidential Election of 1864. The plan called for Confederate agents to cross the Canadian border and set fires on Election Day throughout Chicago, Cincinnati, Boston and New York City. His hope was to create enough fear and confusion in the city for the Copperheads to move in and seize the important buildings in the area. The original plot included plans to occupy Federal buildings and steal weapons from Federal arsenals that would be used arm their supporters. The insurgents would then raise a Confederate Flag over City Hall and declare that New York City had left the Union and had aligned itself with the Confederacy. If successful, a scheme of this magnitude might influence Lincoln or his opponent General George B. McClellan to stop the war and sue for peace.

Meanwhile, on October 15, 1864, an editorial appeared in the Richmond Whig calling for Confederates to retaliate against Northern cities for the recent atrocities committed by Federal soldiers on hundreds of farms in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. The editorial called on Confederate agents in Canada to “burn one of the chief cities of the enemy, say Boston, Philadelphia, or Cincinnati, and let its fate hang over the others as a warning of what may be done to them, if the present system of war on the part of the enemy is continued.”

Eight Confederates were selected from various Regiments who had proven to be very capable behind the lines of the enemy. The men proceeded to Canada. Entrusted with the command of the New York City operations were Lieutenant Colonel Robert Martin and Lieutenant John W. Headley, two young, but battle tested Officers who had served under famed Kentucky Cavalry General John Hunt Morgan.

|

| Robert Martin |

These men had been specifically ordered from Virginia to undertake whatever operations Thompson conceived. They were joined by 6 other Confederate Officers, all who had recently escaped from various Federal Prison Camps before making their way into Canada.

Among the other 6 Confederates was my 5th cousin 6x Captain Robert Cobb Kennedy, who had recently escaped from Johnson's Island Prison Camp.

Robert Cobb Kennedy was born in Columbia, Georgia on October 25, 1835. Robert was the 2nd cousin of Confederate Major General Howell Cobb, who I've previously written about. Shortly after his birth, his family moved to Alabama. Sometime before 1850, they relocated to Claiborne, Louisiana. Prior to the start of the Civil War, Robert enjoyed the life of a Louisiana Planter. He spent two years at the United States Military Academy at West Point before returning home to Louisiana. When the war broke out, he joined the ranks of 1st Louisiana Infantry as a Lieutenant. He was promptly promoted to the rank of Captain sometime before 1863.

In October of 1863, Robert was dispatched to Chattanooga, Tennessee where he served under General Joseph Wheeler. He was captured by Federal officers while on detail near Decatur, Alabama and confined to Johnson's Island Prison Camp.

Once confined at Johnson's Island, Robert began to boast that "he had been in half a dozen Union Prison Camps". He also began plotting his escape. Johnson's Island Prison Camp was located on a remote island about 2.5 miles outside of Sandusky, Ohio. Its location on the water provided a natural barrier on all sides. It was also constructed on limestone bedrock, which made tunneling virtually impossible. If Robert was to escape, he would have to orchestrate a masterful plan. The only way out was over the fence, but once over the fence, the icy waters of the bay proved to be another obstacle to freedom.

Using a piece of scrap wood, Robert constructed a make-shift ladder. On the night of October 4, 1864, Robert and accomplice Turk Smith carried the ladder to the wall. Smith held the ladder while Robert climbed up and over the stockade wall. Once over, he ran to a skiff that was hidden amongst the rocks and pushed off into the bay. Robert traveled east and headed along the shoreline of Lake Erie through Ohio and into New York. When he made it to Buffalo, he crossed the border into Canada and made his way to Toronto to convene with Jacob Thompson.

The "Confederate Army of Manhattan" met at the St. Dennis Hotel at Broadway and East 11th Street. There they began preparations to burn New York City. Each man was instructed to take several rooms in various hotels throughout the south side of the city.

On October 28, 1864, the Confederate agents met with James A. McMaster, editor of the Freeman's Journal, in his New York City Office. McMaster was a known New York Copperhead. The men discussed the upcoming election day plot to burn New York. McMaster’s role in the plot was to activate a secret army of 25,000 Copperhead New Yorkers who would raise the First National Flag of the Confederacy over New York City Hall once the fires had disrupted the election.

Five days before the election, New York City officials released a telegram from U.S. Secretary of State William Stewart:

After President Lincoln caught wind of the plan, he ensured the plot would never reach fruition by sending thousands of Federal troops into New York City to make sure the election was peaceful. On November 6th, a Federal detachment of nearly 10,000 men, commanded by Major General Benjamin "Beast” Butler arrived in New York City and anchored off Manhattan. Ferryboats filled with Infantry were stationed in the East and Hudson Rivers. Gunboats were stationed off the Battery to protect downtown and the new Central Park reservoir was closely guarded. With the city crawling with Union Soldiers, the Confederate infiltrators could only stand by and watch the parades that had been organized by supporters of Lincoln or McClellan. Election day came and went and although Lincoln didn't carry New York City, he was elected for a second term.

In his memoir published in 1905, Lieutenant John W. Headley stated: "We expected to take an active part in an attempt by the Sons of Liberty to inaugurate a revolution in New York City, to be made on the day of the presidential election, November 8th. Thompson sent Martin with seven selected Confederate officers, myself included, to report for duty to the leaders. Martin was in charge of the whole thing. The plot was exposed by Northern secret service agents, and General Butler with ten thousand troops arrived, which so disconcerted the Sons of liberty that the attempt was postponed. We remained in the city awaiting events, but the situation being chaotic we had nothing to do."

Most of the Copperheads backed out of the plan, but a few of the Confederate agents stayed behind and were determined to carry out their incendiary plan. The atrocities committed by Federal troops in Atlanta under the command of General William T. Sherman and also in the Shenandoah Valley under the command of General Phil Sheridan, were too much for these men to just sit back and watch. Headley's memoir stated, "When Sherman burned Atlanta, November 15th, Martin proposed to fire New York City. This was agreed to by Thompson, and the project was finally undertaken by Martin and five others, including myself."

The men originally selected Thanksgiving Day, but ultimately settled for “Evacuation Day,” a New York holiday that celebrated the British evacuation of New York City during the Revolutionary War. Their weapons of choice were 144 small vials of "Greek Fire," a special chemical combination that looked like water but when exposed to air, after a short delay, would ignite in flames. The Confederates practiced with the vials by throwing them on boards outside a rented house in Central Park. Once the glass vials broke and the chemical compound was exposed to oxygen, flames erupted and engulfed the boards in flames.

The men were instructed to use the bed in each room, pile it with clothing, rugs, drapes, newspapers, and any other flammable items. Next, they were to empty two vials of the solution on top of the pile. In a few minutes, flames would ignite the pile. This delay would give them plenty of time to escape unnoticed before the fire started. After starting one fire, the man would then proceed to the next location and do the same. Each man would be capable of setting off several fires blocks from each other. Their targets were more than 20 business and hotels, most of them along Broadway near or around City Hall.

The Confederates began setting their fires shortly after 7:00pm on November 25, 1864. This time was agreed upon since none of the hotel patrons would be asleep in their beds when the fires were set. Even though the men wanted to enact revenge upon the North, they did not want there to be any loss of lives in their retaliation. John W. Headley's memoir recants their actions:

Captain Kennedy's targets were the Love-Joy's Hotel, Tammany Hall, and the New England House. As a last minute thought, Kennedy decided to go into P.T. Barnum's Museum and go up to the fifth floor where he could obtain a good view of Broadway and several of the fires. After a few moments he made his way down a stairwell where he proceeded to ignite the "Greek Fire." Panic ensued, with people rushing out of the building in a frenzy, but no one was killed or seriously injured and the fire was quickly extinguished. Unfortunately for P.T. Barnum, the museum burned to the ground in another mysterious fire on July 13, 1865.

A full listing of all the over 35 properties damaged in the fire reads as follows: Belmont Hotel, Love-Joy's Hotel, New England House, The City Hotel, The Everett House, The United States Hotel, The Astor House, P.T Barnum's American Museum, Niblo's Garden Theatre, The Metropolitan Hotel, The LaFarge House, St. James Hotel, St. Nicholas Hotel, Tammany Hall, The Fifth Avenue Hotel, Hanford Hotel, Winter Garder Theatre, Planting Mill, Howard Hotel, The Brandreth House, Franche's Hotel, Wallack's Theatre, Collamore House, Panorama, New York Harbor, 2 Hay stacks on Moore St., Hoffman House, St. Denis, Fifth Ward Museum Hotel, Palace Garden Theatre, Albemarle Hotel, Hotel Victoria, Gilsey, The Grand, The Coleman House, The Martinique and the St. George Cricket Club.

Most of the fires fizzled out on their own or failed to ignite completely. The Confederates forgot to open the windows in any of the rooms, which robbed the flames of a steady supply of oxygen. Poor methods of practice could also have been a cause of the failure. There was some light panic spread along Broadway as word of the attack began to get out. Shouts of “Fire, Fire” coming from the LaFarge hotel disrupted the performance of Julius Caesar, starring John Wilkes Booth at the adjacent Winter Garden Theatre.

The Confederate operatives returned to their Central Park house amid word from New York citizens that this surely had been a Confederate plan. By the next morning newspapers were reporting that detectives were looking for the Rebel plotters. The men laid low until Saturday, November 28th, when they made their way to the rail depot and stealthily boarded a north-bound train bound for Buffalo, where they crossed the suspension bridge into Canada. Most of the men kept a low profile in Canada for a few weeks before returning to the South. Robert Cobb Kennedy boasted about his involvement in the burnings during several drunken rants in Canada. His loose lips coupled with a $25,000 reward led to his capture a few weeks later as he was trying to buy a train ticket in Detroit. He was confined to Fort Lafayette on Governor's Island in New York Harbor where he awaited trial.

Since he was the only one caught, he became the poster boy for the New York City fires. Yellow journalism began to paint a very different picture of the "Southern Terrorist." The press demonized him. An article from the New York Times dated February 28, 1865 describes Kennedy as follows:

During his confinement at Fort Lafayette, Kennedy spent his time writing a journal from "Room No. 1". Most of the pages were destroyed at his request but a few pages managed to survive. Below are various entries that shine a light on Kennedy's thoughts during his confinement.

On March 20, 1865, the Military Commission returned their verdict. They believed that Robert Cobb Kennedy should hang for his participation in the plot to burn New York City. His execution was set for Saturday, March 25th. All that was left to do was erect the gallows. Below are the official Military Commission documents that show Kennedy's trial and verdict:

During the course of the next five days, Kennedy went through nearly every emotion possible. He furiously fired off letters to friends and family. On March 23, 1865 a photographer visited Kennedy and took the photo below. A few hours before he went to the gallows, Kennedy sent copies of the photo along with locks of his hair, to friends and family in the South.

Kennedy still maintained hope that President Lincoln would commute his sentence since he had been captured on his way home and not while trying to exact more revenge on the North. On the night before his execution, Kennedy scribbled out a note to the detectives who helped catch him. It reads as follows:

The next morning was told that the hour had arrived. "All right," said he, "I'm ready; I'm prepared for this thing; tie my arms;" and then, after a moment's quiet, he shouted. "This is hard for you damned Yankees to use me to. I'm a regular soldier in the Confederate army, and have been since the war."

Captain Robert Cobb Kennedy, dressed in a civilian suit made of Confederate gray wool, made his way to the gallows where a small contingent of reporters awaited the spectacle. A Federal Captain read the verdict aloud, during which Kennedy sneered "it's a damned lie." After a short prayer, Kennedy asked to speak a few last words. "Colonel, i wish to make a statement. Gentlemen, this is judicial murder. Colonel, I am ready. This is a judicial, cowardly murder. There's no occasion for the United States to treat me this way. I say Colonel, can't you get me a drink before I go up?" The noose was placed around his neck and the black hood pulled over his face. Kennedy began to sing a few lines of verse:

Three Cousins Murdered by Yankees in the Old Albemarle Region of North Carolina

Robert Cobb Kennedy was just 29 years old at the time of his execution. He was buried in an unmarked grave on Governor's Island. In the late 1870's all the graves on the island were disinterred and re-buried in Cypress Hills National Cemetery, where Kennedy currently lies in an unmarked grave.

Here's my relation to Robert Cobb Kennedy:

Kennedy was just one of eight arsonists, but he was the only one ever punished for the attempt to burn New York. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Martin, the originator of the burning plot, was arrested after the war and also confined to Fort Lafayette. Apparently Martin was also supposed to follow Kennedy's footsteps to the gallows, but his trial never took place. Martin was released from Fort Lafayette in 1866 due to lack of sufficient evidence against him. Martin later moved to New York where he died at age 61 due to an old war ailment. John W. Headley returned to Kentucky after the end of the Civil War where he served one term as Kentucky's Secretary of State before moving to Los Angeles, California where he died in 1930 at the age of 90. His 1905 memoir attempts to justify the plot to burn New York, stating in all capital letters:

Robert Cobb Kennedy was born in Columbia, Georgia on October 25, 1835. Robert was the 2nd cousin of Confederate Major General Howell Cobb, who I've previously written about. Shortly after his birth, his family moved to Alabama. Sometime before 1850, they relocated to Claiborne, Louisiana. Prior to the start of the Civil War, Robert enjoyed the life of a Louisiana Planter. He spent two years at the United States Military Academy at West Point before returning home to Louisiana. When the war broke out, he joined the ranks of 1st Louisiana Infantry as a Lieutenant. He was promptly promoted to the rank of Captain sometime before 1863.

In October of 1863, Robert was dispatched to Chattanooga, Tennessee where he served under General Joseph Wheeler. He was captured by Federal officers while on detail near Decatur, Alabama and confined to Johnson's Island Prison Camp.

|

| Artist's rendition of Johnson's Island Prison Camp |

Once confined at Johnson's Island, Robert began to boast that "he had been in half a dozen Union Prison Camps". He also began plotting his escape. Johnson's Island Prison Camp was located on a remote island about 2.5 miles outside of Sandusky, Ohio. Its location on the water provided a natural barrier on all sides. It was also constructed on limestone bedrock, which made tunneling virtually impossible. If Robert was to escape, he would have to orchestrate a masterful plan. The only way out was over the fence, but once over the fence, the icy waters of the bay proved to be another obstacle to freedom.

Using a piece of scrap wood, Robert constructed a make-shift ladder. On the night of October 4, 1864, Robert and accomplice Turk Smith carried the ladder to the wall. Smith held the ladder while Robert climbed up and over the stockade wall. Once over, he ran to a skiff that was hidden amongst the rocks and pushed off into the bay. Robert traveled east and headed along the shoreline of Lake Erie through Ohio and into New York. When he made it to Buffalo, he crossed the border into Canada and made his way to Toronto to convene with Jacob Thompson.

The "Confederate Army of Manhattan" met at the St. Dennis Hotel at Broadway and East 11th Street. There they began preparations to burn New York City. Each man was instructed to take several rooms in various hotels throughout the south side of the city.

On October 28, 1864, the Confederate agents met with James A. McMaster, editor of the Freeman's Journal, in his New York City Office. McMaster was a known New York Copperhead. The men discussed the upcoming election day plot to burn New York. McMaster’s role in the plot was to activate a secret army of 25,000 Copperhead New Yorkers who would raise the First National Flag of the Confederacy over New York City Hall once the fires had disrupted the election.

Five days before the election, New York City officials released a telegram from U.S. Secretary of State William Stewart:

“This Department has received information from the British Provinces (Canada) to the effect that there is a conspiracy on foot to set fire to the principal cities in the Northern States on the day of the Presidential election. It is my duty to communicate this information to you.”

After President Lincoln caught wind of the plan, he ensured the plot would never reach fruition by sending thousands of Federal troops into New York City to make sure the election was peaceful. On November 6th, a Federal detachment of nearly 10,000 men, commanded by Major General Benjamin "Beast” Butler arrived in New York City and anchored off Manhattan. Ferryboats filled with Infantry were stationed in the East and Hudson Rivers. Gunboats were stationed off the Battery to protect downtown and the new Central Park reservoir was closely guarded. With the city crawling with Union Soldiers, the Confederate infiltrators could only stand by and watch the parades that had been organized by supporters of Lincoln or McClellan. Election day came and went and although Lincoln didn't carry New York City, he was elected for a second term.

|

| Pro-Lincoln Poster from the 1864 Campaign |

In his memoir published in 1905, Lieutenant John W. Headley stated: "We expected to take an active part in an attempt by the Sons of Liberty to inaugurate a revolution in New York City, to be made on the day of the presidential election, November 8th. Thompson sent Martin with seven selected Confederate officers, myself included, to report for duty to the leaders. Martin was in charge of the whole thing. The plot was exposed by Northern secret service agents, and General Butler with ten thousand troops arrived, which so disconcerted the Sons of liberty that the attempt was postponed. We remained in the city awaiting events, but the situation being chaotic we had nothing to do."

Most of the Copperheads backed out of the plan, but a few of the Confederate agents stayed behind and were determined to carry out their incendiary plan. The atrocities committed by Federal troops in Atlanta under the command of General William T. Sherman and also in the Shenandoah Valley under the command of General Phil Sheridan, were too much for these men to just sit back and watch. Headley's memoir stated, "When Sherman burned Atlanta, November 15th, Martin proposed to fire New York City. This was agreed to by Thompson, and the project was finally undertaken by Martin and five others, including myself."

|

| Aerial view of NYC looking south from St. Paul steeple. P.T. Barnum's Museum is on the far left |

The men originally selected Thanksgiving Day, but ultimately settled for “Evacuation Day,” a New York holiday that celebrated the British evacuation of New York City during the Revolutionary War. Their weapons of choice were 144 small vials of "Greek Fire," a special chemical combination that looked like water but when exposed to air, after a short delay, would ignite in flames. The Confederates practiced with the vials by throwing them on boards outside a rented house in Central Park. Once the glass vials broke and the chemical compound was exposed to oxygen, flames erupted and engulfed the boards in flames.

The men were instructed to use the bed in each room, pile it with clothing, rugs, drapes, newspapers, and any other flammable items. Next, they were to empty two vials of the solution on top of the pile. In a few minutes, flames would ignite the pile. This delay would give them plenty of time to escape unnoticed before the fire started. After starting one fire, the man would then proceed to the next location and do the same. Each man would be capable of setting off several fires blocks from each other. Their targets were more than 20 business and hotels, most of them along Broadway near or around City Hall.

|

| A map showing the targeted fires with some modern day landmarks. |

The Confederates began setting their fires shortly after 7:00pm on November 25, 1864. This time was agreed upon since none of the hotel patrons would be asleep in their beds when the fires were set. Even though the men wanted to enact revenge upon the North, they did not want there to be any loss of lives in their retaliation. John W. Headley's memoir recants their actions:

"On the evening of November 25th, I went to my room in the Astor house, at twenty minutes after seven. I hung the bedclothes over the foot-board, piles chairs, drawers, and other material on the bed, stuffed newspapers into the heap, and poured a bottle of turpentine over the whole mass. I then opened a bottle of "Greek Fire" and quickly spilled it on top. It blazed instantly. I locked the door and went downstairs. Leaving the key at the office, as usual, I passed out. I did likewise at the city Hotel, Everett House, and United States Hotel. At the same time Martin operated at the Hoffman House, Fifth Avenue, St. Denis, and others. Altogether our little band fired nineteen hotels. Captain Kennedy went to Barnum's Museum and broke a bottle on the stairway, creating a panic. Lieutenant Harrington did the same at the Metropolitan Theater, and Lieutenant Ashbrook at Niblo's Garden. I threw several bottles into barges of hay, and caused the only fires, for, strange to say, nothing serious resulted from any of the hotel fires. It was not discovered until the next day, at the Astor House, that my room had been set on fire. Our reliance on "Greek Fire" was the cause of the failure. We found that it could not be depended upon as an agent for incendiary work."

Captain Kennedy's targets were the Love-Joy's Hotel, Tammany Hall, and the New England House. As a last minute thought, Kennedy decided to go into P.T. Barnum's Museum and go up to the fifth floor where he could obtain a good view of Broadway and several of the fires. After a few moments he made his way down a stairwell where he proceeded to ignite the "Greek Fire." Panic ensued, with people rushing out of the building in a frenzy, but no one was killed or seriously injured and the fire was quickly extinguished. Unfortunately for P.T. Barnum, the museum burned to the ground in another mysterious fire on July 13, 1865.

|

| P.T. Barnum's American Museum in 1858 |

A full listing of all the over 35 properties damaged in the fire reads as follows: Belmont Hotel, Love-Joy's Hotel, New England House, The City Hotel, The Everett House, The United States Hotel, The Astor House, P.T Barnum's American Museum, Niblo's Garden Theatre, The Metropolitan Hotel, The LaFarge House, St. James Hotel, St. Nicholas Hotel, Tammany Hall, The Fifth Avenue Hotel, Hanford Hotel, Winter Garder Theatre, Planting Mill, Howard Hotel, The Brandreth House, Franche's Hotel, Wallack's Theatre, Collamore House, Panorama, New York Harbor, 2 Hay stacks on Moore St., Hoffman House, St. Denis, Fifth Ward Museum Hotel, Palace Garden Theatre, Albemarle Hotel, Hotel Victoria, Gilsey, The Grand, The Coleman House, The Martinique and the St. George Cricket Club.

Most of the fires fizzled out on their own or failed to ignite completely. The Confederates forgot to open the windows in any of the rooms, which robbed the flames of a steady supply of oxygen. Poor methods of practice could also have been a cause of the failure. There was some light panic spread along Broadway as word of the attack began to get out. Shouts of “Fire, Fire” coming from the LaFarge hotel disrupted the performance of Julius Caesar, starring John Wilkes Booth at the adjacent Winter Garden Theatre.

The Confederate operatives returned to their Central Park house amid word from New York citizens that this surely had been a Confederate plan. By the next morning newspapers were reporting that detectives were looking for the Rebel plotters. The men laid low until Saturday, November 28th, when they made their way to the rail depot and stealthily boarded a north-bound train bound for Buffalo, where they crossed the suspension bridge into Canada. Most of the men kept a low profile in Canada for a few weeks before returning to the South. Robert Cobb Kennedy boasted about his involvement in the burnings during several drunken rants in Canada. His loose lips coupled with a $25,000 reward led to his capture a few weeks later as he was trying to buy a train ticket in Detroit. He was confined to Fort Lafayette on Governor's Island in New York Harbor where he awaited trial.

|

| Fort Lafayette seen from the Brooklyn shore |

Since he was the only one caught, he became the poster boy for the New York City fires. Yellow journalism began to paint a very different picture of the "Southern Terrorist." The press demonized him. An article from the New York Times dated February 28, 1865 describes Kennedy as follows:

"Mr. Kennedy is a man of apparently 30 years of age, with an exceedingly unprepossessing countenance. His head is well shaped, but his brow is lowering, his eyes deep sunken and his look unsteady. Evidently a keen-witted, desperate man, he combines the cunning and the enthusiasm of a fanatic, with the lack of moral principle characteristic of many Southern Hotspurs, whose former college experiences, and most recent hotel-burning plots are somewhat familiar to our readers. Kennedy is well connected at the South, is a relative, a nephew we believe, of Howell Cobb, and was educated at the expense of the United States, at West Point, where he remained two years, leaving at that partial period of study in consequence of mental or physical inability. While there he made the acquaintance of Ex. Brig. Gen. E.W. Stoughton, who courteously proffered his services as counsel for his ancient friend in his present needy hour. During Kennedy’s confinement here, while awaiting trial, he made sundry foolish admissions, wrote several letters which have told against him, and in general did, either intentionally or indiscreetly, many things, which seem to have rendered his conviction almost a matter of entire certainty. "Kennedy was tried in front of a Military Commission led by Federal General Fitz-Henry Warren. A former classmate at West Point, Brigadier General Edward Stoughton represented him at the trial. The proceedings began on January 17, 1865 and ended in early March. During the trial Kennedy made a full confession, but refused to name anyone else that was involved in the plot. His confession reads:

"After my escape from Johnson's Island I went to Canada, where I met a number of Confederates. They asked me if I was willing to go on an expedition. I replied, "Yes; if it is in the service of my country." They said, "It's all right", but gave no intimation of its nature, nor did I ask for any. I was then sent to New York, where I staid some time. They were eight men in our party, of whom two fled to Canada. After we had been in New York three weeks we were told that the object of the expedition was to retaliate on the North for the atrocities in the Shenandoah Valley. It was designed to set fire to the city on the night of the Presidential election, but the phosphorus was not ready and it was put off until the 25th of November. I was stopping at the Belmont House, but moved into Prince street. I set fire to four places-Barnum's Museum, Lovejoy's Hotel, Tammany Hotel, and the New England House. The others only started fires in the house where each was lodging and then ran off. Had they all done as I did we would have had thirty-two fires and played a huge joke on the fire department. I know that I am to be hung for setting fire to Barnum's Museum, but that was only a joke. I had no idea of doing it. I had been drinking and went it there with a friend, and, just to scare the people, I emptied a bottle of phosphorus on the floor. We knew it wouldn't set fire to the wood, for we had tried it before, and at one time concluded to give the whole thing up.

There was no fiendishness about it. After setting fire to my flour places I walked the streets all night and went to the Exchange Hotel early in the morning. We all met there that morning and the next night. My friend and I had rooms there, but was sat in the office nearly all the time reading the papers, while we were watched by the detectives of whom hotel was full. I expected to die then, and if I had it would have been all right; but now it seems rather hard. I escaped to Canada, and was glad enough when I crossed the bridge in safety.

I desired, however, to return to my command, and started with my friend for the Confederacy via Detroit. Just before entering the city he received an intimation that the detectives were on the lookout for us, and giving me signal, he jumped from the cars. I didn't notice the signal, but kept on and arrested in the depot.

wish to say that killing women and children was the last thing though of. We wanted to let the people of the North understand that there are two sides to this war, and that they can't be rolling in wealth and comfort while we at the South are bearing all the hardships and privations.

In retaliation for Sheridan's atrocities in the Shenandoah Valley we desired to destroy property, not the lives of women and children, although that would of course have followed in its train."

Done in the presence of Lieutenant Colonel Martin Burke.

OFFICE COMMISSARY-GENERAL OF PRISONERS,

Washington, D. C., March 25, 1865.

During his confinement at Fort Lafayette, Kennedy spent his time writing a journal from "Room No. 1". Most of the pages were destroyed at his request but a few pages managed to survive. Below are various entries that shine a light on Kennedy's thoughts during his confinement.

IN HELL, March 2, 1865.

Having slept the greater portion of the day, I cannot sleep to-night, and as I have the conveniences at hand, propose committing some of my thoughts to paper. In thinking all over the circumstances of my trial. I must believe the verdict of my judges will be Not Guilty. But thinking also that I am a captive in the hands of enemies, who regard it a crime worthy of death to be an officer of the Confederate States Army, I am doubtful of their verdict. In summing up the evidence against me the Judge-Advocate shed tears, and afterwards shook hands, and asked me to pity him, that he merely did his duty, and was not actuated by malicious feelings to prosecute me.

This is all very well, but I must recollect that the same Judge-Advocate, when I was utterly friendless, and looked to him to assist me in my defence, scoffed at any rebutting evidence I proposed introducing. It was only when I was convinced that he intended rendering me no assistance, that I asked the court to grant a delay in order to obtain Gen. Stoughton as counsel. Maj. Bolles, the Judge-Advocate, knows well, that when the evidence for the Government was given I objected to nothing; that a large amount of irrelevant-matter-was introduced into the records of the court which appears as evidence against me. I thought that equal generosity would be extended toward me in making my defence; that I was arraigned, not before a judge and ignorant jurymen, out before intelligent officers of the same honorable profession to which I belong; that the Judge-Advocate, as a man of honor, would suffer me to elicit anything from my witnesses that would throw light in the case before the commission. Fool that I was to imagine anything of the kind. He objected to and debarred the most important part of the testimony I had to offer, viz: the evidence of Smith in regard to having given Hays $15 in gold, and the documents from Canada showing that I had no idea or intention of acting the spy when I entered the territory of the United States. I do not believe that a member of that commission, or Major Bolles, the Judge-Advocate, believes me to have acted as a spy or guerrilla, but I may be pronounced guilty of both charges. If I am executed, it will be nothing less than judicial, brutal, cowardly murder.

March 4.

This is a gala day for my enemies. They will do their best to honor Abraham. and celebrate the recent Union victories. The Federals have obtained possession of Charleston, Wilmington, and other places along our seaboard, but not by valor. Circumstances -- military necessity-caused the Confederates to evacuate them. The dogs ought to remember that they did not take Charleston by open warfare, that Gillmore & Co. have hammered in vain long at her gates and the "nest of secession" only succumbed when there was an army in its rear. They swear that Charleston made no resistance, without considering that her sons are in the peerless band of Lee. Goddamn them, let them subjugate the South and then triumph.

March 5.

I spent last night in giving a few impression of things during my trial. Here I will state that I will believe Major Bolles was honest in his statements to me; that he acted in accordance with the dictates of duty in pursuing me like a sleuth-hound and was hot actuated by malice or prejudice toward me. The conduct of Gen. Stoughton has been most noble; be came to my assistance when I was utterly friendless. Although I know that I would have done the came to him under a reversal of circumstances. I cannot properly express my gratitude or appreciation of his services. His conduct has almost disarmed me of any malice toward the Yankees, although they have made the fairest portion of my country a desert. Stoughton knows that when at West Point I was not sectional in my feelings or associations; that gentlemen were always welcome to my loom, whether born in Maine or Louisiana. He knows that I think myself right in my present position. If I had been the scoundrel that some New-York journals represent me. would he have so promptly tendered his services as counsel, without expecting a reward? I have no doubt He believed me unable to remunerate him in any manner, and undertook my defence merely through remembrance of "old times." I believe my cause to be a just one -- that it will ultimately succeed I have no doubt. If there is a just God he must favor those who most deserve it. Some detectives came to see me to-night. When asked their opinion of the result of my trial, they replied. "We think it will go against you." As every one knows who happened to know me, their opinion has no effect on me. It is to their interest to convict me. They get a considerable reward in that case.

I wrote to Chief Detective Young to-night to procure an interview between myself and Gen. Beall, C.S.A. I hope the Yankee authorities will grant it. I am much in need of articles Beall could furnish me. The damned vermin are so numerous that I am almost in the condition of Lee's veteran, who wanted a pound of mercurial ointment. Like him I am afraid to sneeze, for fear the damned lice would regard it a gong for dinner, and eat me up.

Oh. never, never, never, will a true Confederate soldier

Forsake his friends or fear his foes;

For while our Lord's Cross proudly floats defiance,

I don't care a damn how the wind blows.

On March 20, 1865, the Military Commission returned their verdict. They believed that Robert Cobb Kennedy should hang for his participation in the plot to burn New York City. His execution was set for Saturday, March 25th. All that was left to do was erect the gallows. Below are the official Military Commission documents that show Kennedy's trial and verdict:

During the course of the next five days, Kennedy went through nearly every emotion possible. He furiously fired off letters to friends and family. On March 23, 1865 a photographer visited Kennedy and took the photo below. A few hours before he went to the gallows, Kennedy sent copies of the photo along with locks of his hair, to friends and family in the South.

|

| Photograph of Robert Cobb Kennedy taken 3/25/1865 |

Kennedy still maintained hope that President Lincoln would commute his sentence since he had been captured on his way home and not while trying to exact more revenge on the North. On the night before his execution, Kennedy scribbled out a note to the detectives who helped catch him. It reads as follows:

"FT. LAFAYETTE, March 25th, 1855.

J.S. Young:

DEAR SIR -- I am much obliged by the sending of that article.

In answer to your desire to ascertain the present state of my feelings towards you and associates. I can only say I bear you no malice. You did your duty as detectives, with, perhaps, as much kindness to me any others would under similar circumstances. Our professions have been different; what appealed right and proper to you seemed unfair and dishonorable to me; for example, the manner in which HAYES was instructed or allowed to act in order to obtain evidence against me.

Be assured I appreciate the many little acts of kindness extended by you and others to Respectfully yours.

R. C. KENNEDY

The next morning was told that the hour had arrived. "All right," said he, "I'm ready; I'm prepared for this thing; tie my arms;" and then, after a moment's quiet, he shouted. "This is hard for you damned Yankees to use me to. I'm a regular soldier in the Confederate army, and have been since the war."

Captain Robert Cobb Kennedy, dressed in a civilian suit made of Confederate gray wool, made his way to the gallows where a small contingent of reporters awaited the spectacle. A Federal Captain read the verdict aloud, during which Kennedy sneered "it's a damned lie." After a short prayer, Kennedy asked to speak a few last words. "Colonel, i wish to make a statement. Gentlemen, this is judicial murder. Colonel, I am ready. This is a judicial, cowardly murder. There's no occasion for the United States to treat me this way. I say Colonel, can't you get me a drink before I go up?" The noose was placed around his neck and the black hood pulled over his face. Kennedy began to sing a few lines of verse:

"Trust to luck, trust to luck.Just after his last word, the counterweight was released and Kennedy's body was yanked off the floorboards, the sharp movement snapping his neck. His death was instantaneous. His body moved gently back and forth for a few moments, was cut down, encoffined and prepared for burial. He happened to be fourth and final known member of my family to be executed by the Federal army during the Civil War. Below is a link to an article about my other 3 family members that were murdered:

Stare fate in the face.

For your heart will be easy

If it's in the right place."

Three Cousins Murdered by Yankees in the Old Albemarle Region of North Carolina

Robert Cobb Kennedy was just 29 years old at the time of his execution. He was buried in an unmarked grave on Governor's Island. In the late 1870's all the graves on the island were disinterred and re-buried in Cypress Hills National Cemetery, where Kennedy currently lies in an unmarked grave.

Here's my relation to Robert Cobb Kennedy:

Robert Cobb Kennedy (1835 - 1865)

is your 5th cousin 6x removed

Elizabeth Lydia Cobb (1815 - 1891)

mother of Robert Cobb Kennedy

Henry Willis Cobb (1774 - 1820)

father of Elizabeth Lydia Cobb

John Cobb (1740 - 1809)

father of Henry Willis Cobb

John Cobb (1700 - 1775)

father of John Cobb

Robert Cobbs (1660 - 1727)

father of John Cobb

Robert Cobbs (1626 - 1682)

father of Robert Cobbs

Ambrose Cobb (1662 - 1718)

son of Robert Cobbs

Robert Cobb (1687 - 1769)

son of Ambrose Cobb

Elizabeth Cobb (1724 - 1780)

daughter of Robert Cobb

Reuben Benjamin Eaton Moss Sr. (1737 - 1819)

son of Elizabeth Cobb

Howell Cobb Moss Sr. (1773 - 1831)

son of Reuben Benjamin Eaton Moss Sr.

Benjamin Lucious Moss (1792 - 1847)

son of Howell Cobb Moss Sr.

James C. Moss (1824 - 1891)

son of Benjamin Lucious Moss

William Allen Moss (1859 - 1931)

son of James C. Moss

Valeria Lee Moss (1890 - 1968)

daughter of William Allen Moss

Phebe Teresa Wheeler Lewis (1918 - 1977)

daughter of Valeria Lee Moss

Joyce Elaine Lewis (1948 - )

daughter of Phebe Teresa Wheeler Lewis

Chip Stokes

You are the son of JoyceKennedy was just one of eight arsonists, but he was the only one ever punished for the attempt to burn New York. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Martin, the originator of the burning plot, was arrested after the war and also confined to Fort Lafayette. Apparently Martin was also supposed to follow Kennedy's footsteps to the gallows, but his trial never took place. Martin was released from Fort Lafayette in 1866 due to lack of sufficient evidence against him. Martin later moved to New York where he died at age 61 due to an old war ailment. John W. Headley returned to Kentucky after the end of the Civil War where he served one term as Kentucky's Secretary of State before moving to Los Angeles, California where he died in 1930 at the age of 90. His 1905 memoir attempts to justify the plot to burn New York, stating in all capital letters:

"TEN DAYS BEFORE THIS ATTEMPT OF CONFEDERATES TO BURN NEW YORK CITY, GENERAL SHERMAN HAD BURNED THE CITY OF ATLANTA, GEORGIA, AND THE NORTHERN PAPERS AND PEOPLE OF THE WAR PARTY WERE IN GREAT GLEE OVER THE MISERIES OF THE SOUTHERN PEOPLE."